PART 3.2

Because of the experience with immunization and the successful eradication of smallpox, Dr. Jonas Salk, and Robert McNamara, past World Bank president, asked, “Why can’t the world be vaccinated the way the United States is?” There were good vaccines but poor global coverage. But the major agencies responsible for childhood immunizations were competing rather than collaborating and the immunization level was stuck at 20%.

PART 3.3

Many different organizations were involved with immunizations brought together by The Task Force for Child Survival starting in 1984. But this coalition fell apart in the 1990s when the agency heads, who had been effective collaborators, turned over. They had to rebuild the coalition that had worked under the auspices of The Task Force.

PART 4.1

Mass vaccination was the tried-and-true approach to smallpox eradication. Mass vaccination success was measured by the percentage of the population that was vaccinated, in order to achieve herd immunity. Most countries, WHO and other multilateral organizations were committed to this approach and operationally tied the goals to this strategic approach.

PART 4.3

When HIV first became prominent as a mysterious disease, people had many theories of how it was spread, almost all of them focused on the “immoral and drug-fueled” sexual activities of highly stigmatized groups. They not only held very strong views but they were absolutely certain that they were right. But the public, politicians and scientists were all challenged to rethink their ideas of spread when confronted by reports that the disease could be transmitted by infusing clotting factors from a donor to a patient with hemophilia.

PART 4.4

In the early 2000’s WHO had adopted the ambitious goal of getting 3 million people on antiretroviral medicines by 2005. But some people thought this was too ambitious a goal and that it could never be achieved. Leaders were afraid of making a mistake and being wrong, so they were hesitant to act until they were certain they could achieve their goal. Yet waiting would cause costly delays as the disease raged on, and prevent otherwise ambitious and very important programs from making progress.

PART 5.2

The polio eradication program relied on strong surveillance efforts to inform vaccination efforts. Surveillance teams worldwide constantly searched for cases in which people had limbs that could not be moved and just hung limply, or cases of “flaccid paralysis.”When they found these cases, they would target vaccination to those regions. This was a very effective strategy when polio was widespread, because almost every case of flaccid paralysis was caused by polio. As vaccination coverage increased, cases of paralytic polio plummeted. As cases of flaccid paralysis began to disappear, polio was declared eliminated from many countries and regions. But in many areas polio persisted.

PART 5.3

Infants were dying in rural health centers because they had complications that couldn't be dealt with in those hospitals. Doctors thought that a way to address this would be to transfer them to a larger hospital with more neonatal capacity. But, when the transfer solution was tried, it turned out that more infants were dying. Lives were not being saved. Babies continued to die because the transportation to the secondary or tertiary facilities took so long. The infants could not survive the trip.

PART 6.1

In the early 1960s, India accounted for nearly 60 percent of the reported smallpox cases in the world. The Indian government had launched the National Smallpox Eradication Program which focused on mass vaccination. By 1966, the Indian government reported approximately 60 million primary vaccinations. Mass vaccination campaigns had become part of the culture, and there was wide trust in this singular approach. However, the number of smallpox cases in India was increasing and India needed a new strategy.

PART 6.2

In Mozambique, there was local distrust of the health clinic. A woman did come into the health clinic to deliver her child but both she and the child died in childbirth. The doctor, Hans Rosling, felt terrible and worried that he would never regain the trust of the people in the surrounding villages. But he learned that it was important for him to return the bodies to the village for a proper burial as a sign of respect for the local culture.

PART 7.1

In early 1974, smallpox outbreaks were appearing in areas of India that had been smallpox-free for months. After a week of plotting the epidemic with pushpins on hand-drawn maps, a pattern emerged. Each outbreak began with a working-age young man who had returned home to his village. These cases were “importations.” The young men had come from—or traveled through—the bordering state of Bihar. Cases were originating in Tatanagar, the company town of the corporate behemoth, Tata Companies. Tatanagar, a city in the state of Bihar, had no centralized government, and no public health structure in place.

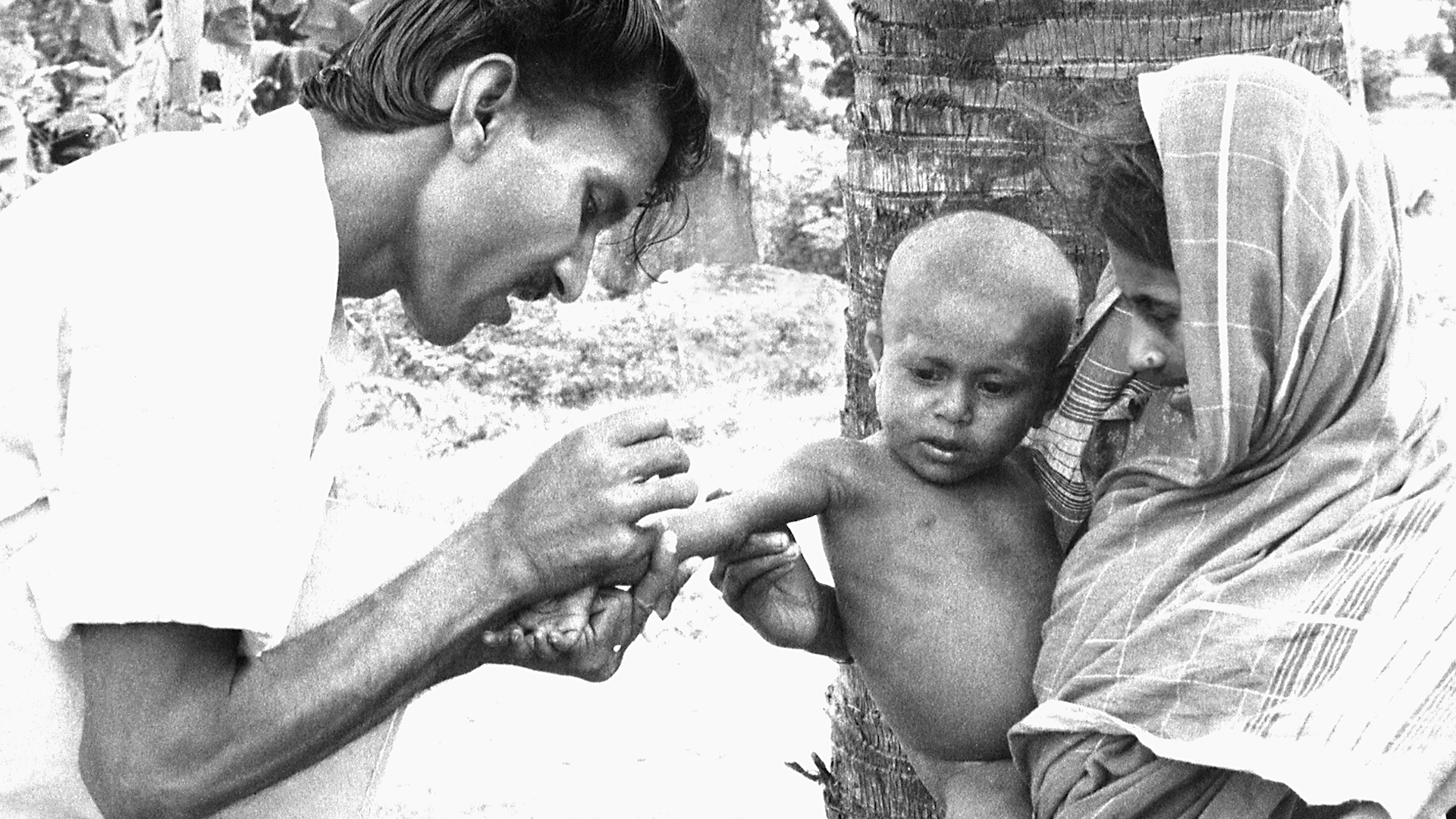

PART 7.2

One of the most challenging things for vaccinations is reaching those who live “at the end of the road”—those who are geographically isolated due to distance or living in hard to access regions. A well-functioning delivery system is one that reaches the patient at the point-of-care. Such a system is essential for adequate access to and availability of vaccines. But, while across Africa, governments and donors are investing billions of dollars to strengthen health systems and make affordable medicines available, government supply chains often struggle to get medicines and supplies through the last mile to the health facilities and to the people who need them most.

PART 8.1

In 1973 India had thousands of cases of smallpox. For a while they were reporting one thousand new cases every day. Leaders of the eradication effort wanted to solicit help from WHO and bring in physicians, epidemiologists and health worker volunteers from other countries to supplement the Indian teams. But the Minister of Health for India felt that India had plenty of health workers and volunteers to do the job and said that people from other countries were not needed. The Minister's support for the smallpox effort was essential, so the team had to convince him to support bringing in workers from other countries without being critical of the great resources India already had.

PART 8.2

In Senegal, young girls usually had to go through a painful process deeply embedded in the culture of their society that served no purpose, and had been going on generation after generation. Girls and women were advocating for an end to this practice of female genital cutting. But their pleas were not enough to convince men throughout the country to stop this traditional cultural practice.

PART 8.3

In February 2016, the World Health Organization declared the Zika virus outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. The Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region was the most affected with more than 700,000 cases reported. In response to the outbreak, the U.S. Government allocated a portion of the funds remaining from the previous Ebola outbreak response to the LAC region. But money was not enough. The region lacked the public health and laboratory infrastructure for disease surveillance, contact tracing, and diagnostics, and needed to quickly build a workforce to respond and prevent future outbreaks.

PART 9.1

An effective vaccine for preventing smallpox had been discovered and tested by 1796. And by the 1970’s widespread vaccination resulted in most people in rich countries being vaccinated and almost completely protected. Smallpox was actually eliminated from developed countries in the 1970s. But the burden of smallpox was inequitably distributed. People in some poor countries remained vulnerable and faced high risks of mortality from smallpox. It was within the poorest communities that smallpox was spread.

PART 9.2

Partners in Health (PIH) is a non-profit global health organization established by Paul Farmer, Jim Kim, and three colleagues to bring health care to the poorest people in low-income countries. PIH believed that these people deserve healthcare that was as good as the healthcare that rich people in the most advanced countries received. They found that poor people living in a shanty town outside of Lima, Peru had very high rates of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDRTB), a disease that was notoriously hard to treat.

PART 9.3

There are medicines that could save the lives of the 500,000 children who die from malaria each year. Most of these children live in the low-income countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. Novartis manufactures the drug, artemisinin-based combination therapy, that is the standard of care for the treatment of P. falciparum malaria, the most deadly form of the disease. Although the global health community has for a long time been skeptical and wary of the private sector where profit was the driving force, Novartis happened to have a CEO who came from the field of global health and was inspired by the vision of global health equity. But neither these malaria-endemic countries nor WHO could afford to purchase commercially the amounts of this drug needed to treat the children who were at risk.