PART 1.1

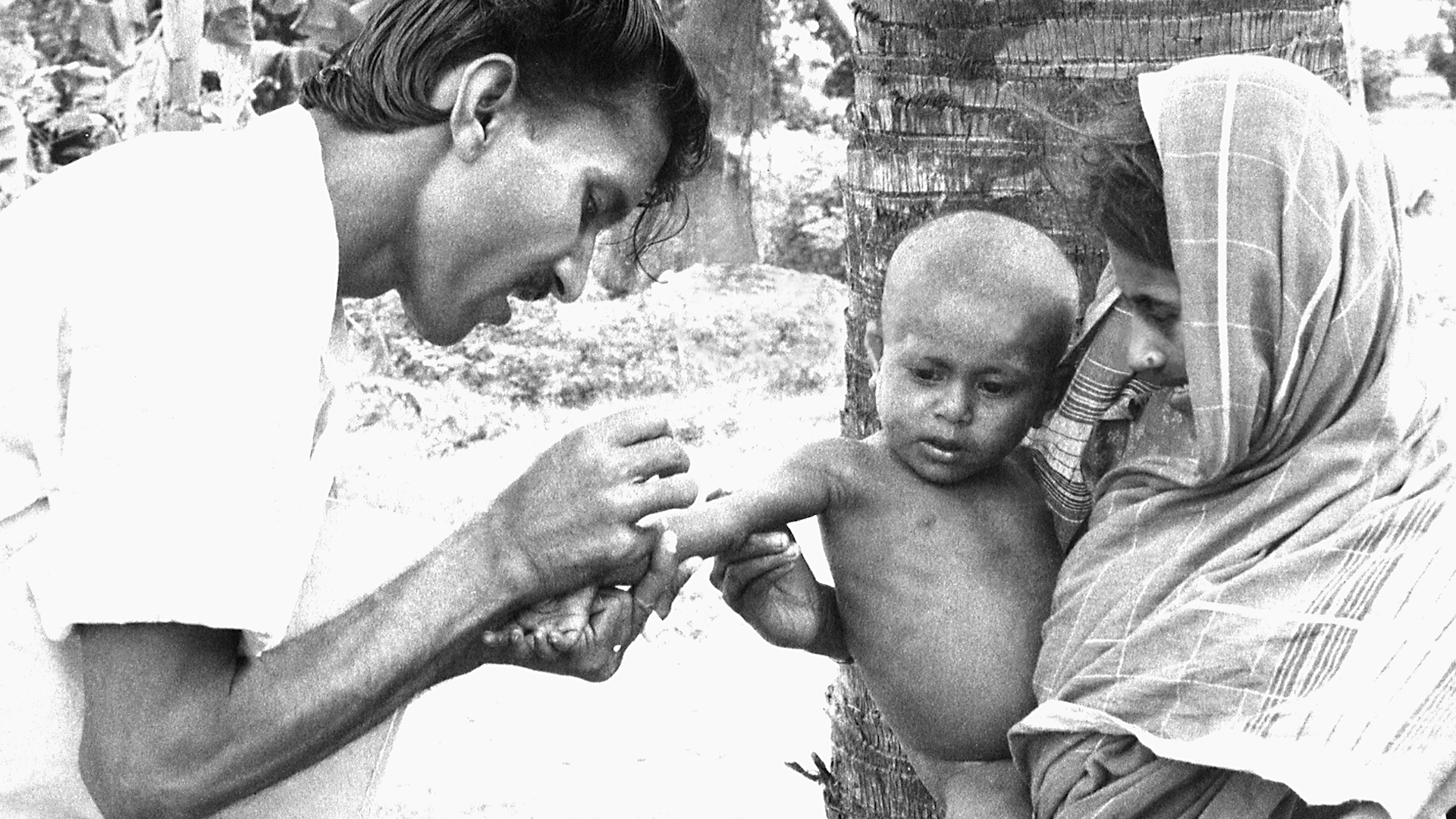

The risk of smallpox was accepted as just an unfortunate part of life. Getting sick was a person’s fate. But in the late 1700s, Dr. Edward Jenner saw things differently and applied a “cause and effect” mindset. After years of observation, he was convinced that having cowpox protected people from contracting smallpox.

PART 2.1

To apply the surveillance and containment strategy, it was necessary to know where the smallpox virus was, which villages had active cases of smallpox. The struggle against smallpox could not be won without knowing where the enemy was and what it was doing. But India did not have accurate surveillance data. Many villages with active cases had not been reported.

PART 3.1

Implementing the smallpox surveillance and containment strategy required massive resources, commitment, and coordination. But moving from a traditional strategy, used for over a century and a half with clearly defined roles for every participant, to a new strategy simply seemed too labor intensive and impossible. This required mobilizing and coordinating hundreds of thousands of implementers with a gradual increase in the number of people involved.

PART 4.1

Mass vaccination was the tried-and-true approach to smallpox eradication. Mass vaccination success was measured by the percentage of the population that was vaccinated, in order to achieve herd immunity. Most countries, WHO and other multilateral organizations were committed to this approach and operationally tied the goals to this strategic approach.

PART 5.1

In the battle to eradicate smallpox in India in 1974, finding and containing thousands of outbreaks was the key to getting smallpox under control. In mid 1974, the number of new outbreaks was starting to decrease slightly. The strategy of surveillance and containment - which included a massive workforce, tireless efforts, and rewards for identifying new cases - was paying off. But then we started to notice that members of previously vaccinated families were still coming down with smallpox. We should not have been seeing these new cases.

PART 6.1

In the early 1960s, India accounted for nearly 60 percent of the reported smallpox cases in the world. The Indian government had launched the National Smallpox Eradication Program which focused on mass vaccination. By 1966, the Indian government reported approximately 60 million primary vaccinations. Mass vaccination campaigns had become part of the culture, and there was wide trust in this singular approach. However, the number of smallpox cases in India was increasing and India needed a new strategy.

PART 7.1

In early 1974, smallpox outbreaks were appearing in areas of India that had been smallpox-free for months. After a week of plotting the epidemic with pushpins on hand-drawn maps, a pattern emerged. Each outbreak began with a working-age young man who had returned home to his village. These cases were “importations.” The young men had come from—or traveled through—the bordering state of Bihar. Cases were originating in Tatanagar, the company town of the corporate behemoth, Tata Companies. Tatanagar, a city in the state of Bihar, had no centralized government, and no public health structure in place.

PART 8.1

In 1973 India had thousands of cases of smallpox. For a while they were reporting one thousand new cases every day. Leaders of the eradication effort wanted to solicit help from WHO and bring in physicians, epidemiologists and health worker volunteers from other countries to supplement the Indian teams. But the Minister of Health for India felt that India had plenty of health workers and volunteers to do the job and said that people from other countries were not needed. The Minister's support for the smallpox effort was essential, so the team had to convince him to support bringing in workers from other countries without being critical of the great resources India already had.